Drawing in Space: The Remarkable Sculptures of Ruth Asawa

- artandcakela

- Aug 22, 2025

- 5 min read

By Betty Ann Brown

An artist is an ordinary person who can take ordinary things and make them special.

~Ruth Asawa

*A circular metallic shape composed of curving branch-like lines gathered to a single point in the center and ending in fragile, threadlike appendages. It hangs on a wall and the shadows it casts seem to extend the thinner lines far below its circumference.

*Another circle, this one seated on a pedestal. It’s composed of gold-filled wire and resembles a royal crown or, perhaps, a dimensional collar, glittering under the bright museum lights.

*A string of five hollow shapes suspended like a gigantic, beaded necklace. Two of its lobes contain small spheres, also hollow. Ghostlike shadows shimmer on the wall behind it, continuing the sculptural space into another dimension.

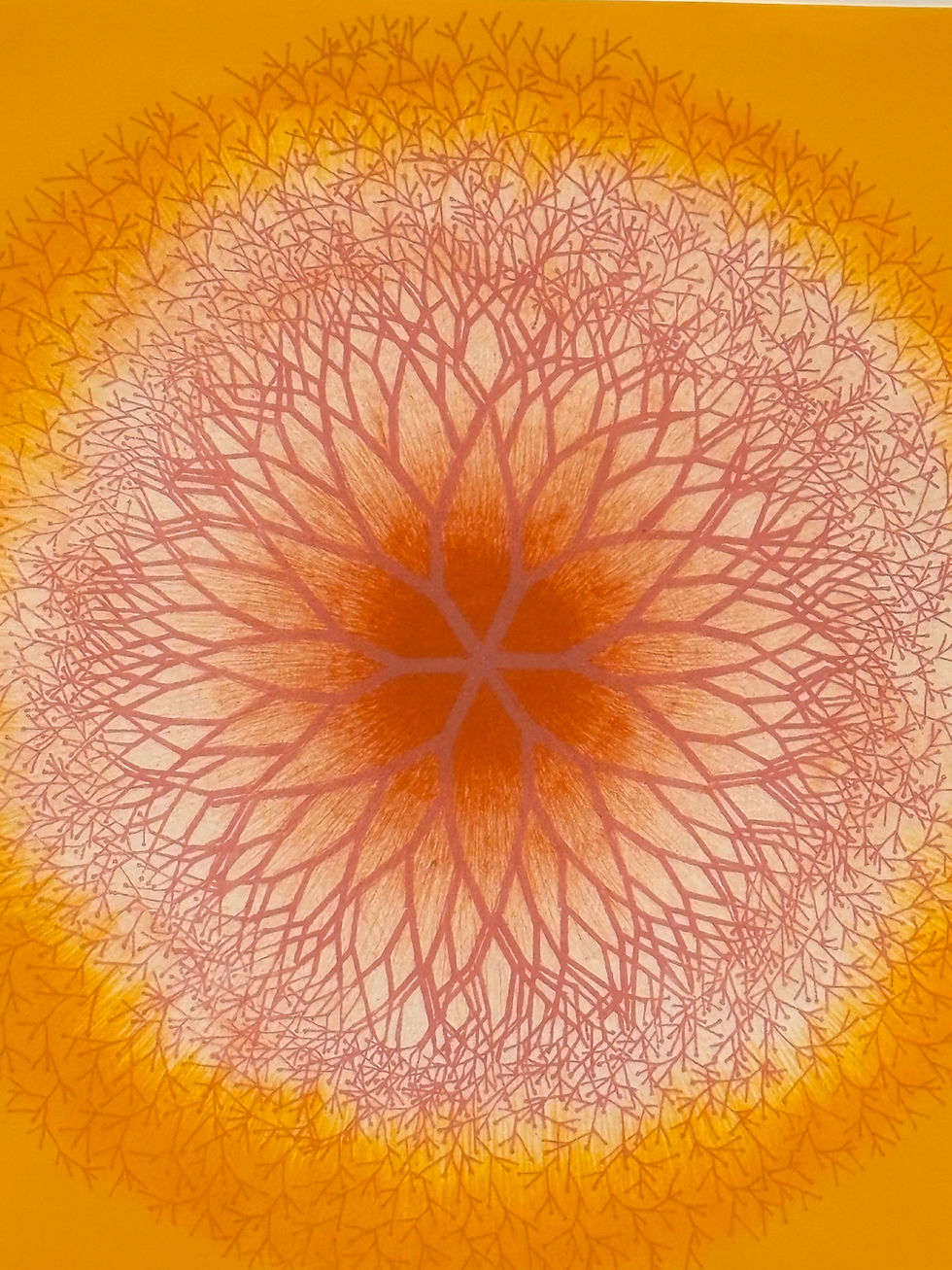

*A glowing golden lithograph presents a fiery red center behind thick pink prongs that push outward into smaller, spidery thin extensions. The color adds a dynamism largely absent from the artist’s sculpture work—but the treelike flow is the same.

The creator of these four artworks is Ruth Asawa (1926-2013), a California artist who was born in Norwalk and spent most of her adult life in San Francisco. She was ripped from her childhood home by the US government in 1946 because of her Japanese ancestry. Most of the family was incarcerated with her in detention centers in California, then Arizona, but father was imprisoned in another internment camp. Asawa didn’t know where or how he was for years.

Asawa left the camp for the Midwest, where she trained to be a teacher. When she realized she couldn’t get a teaching certificate there (because of her Japanese ancestry), she traveled to the avant-garde refuge of Black Mountain College in North Carolina. While there, she studied with Joseph Albers, Merce Cunningham, and Buckminster Fuller. At one point, she traveled to Mexico, where she learned a basketry crochet technique from the indigenous people there. On her return to North Carolina, she began use wire to crochet abstract forms. (There is a great photograph by Bacia Stepner Edelman of Albers’ 1946 demonstration on the use of wire.)

In 1949, Asawa moved to Northern California with architect Albert Lanier, who became her husband and fathered all six of their children. The couple chose Northern California because they knew it was a place that would welcome a bi-racial couple like themselves. Asawa continued making her art in San Francisco but also became a passionately committed art teacher. She was instrumental in the 1982 founding of the San Francisco School of the Arts. In 2010, it was renamed the Ruth Asawa San Francisco School of the Arts in her honor. Like many of her teachers at Black Mountain College, Asawa considered teaching a collaborative enterprise. She extended her community collaboration in six public art projects that adorn her beloved city today.

Like many modernists, Asawa was interested in the relationship between art and science. Many of her works depict what Romanian-American scientist Adrian Bejan calls the Constructal Law. Bejan studies the “predictable patterns” in nature, from tree roots to rivers to human arteries. He observes that “Everything that moves, whether animate or inanimate, is a flow system” created to move liquids from one point to another (whether the liquid is water or blood or even lightning-born electricity.) The flow system “has a treelike pattern to facilitate the liquid that flows through it and its structure.” According to Bejan, “The designs we see in nature are not the result of chance. They rise naturally, spontaneously, because they enhance access to flow…Constructal Law sweeps the entire mosaic of nature, from inanimate rivers to animate designs...”

Most of Ruth Asawa’s artworks are untitled, including three of the four pieces described at the beginning of this essay. I will refer to them by what they evoke to me: Bronze Wire Circle, Gold Wire Crown, Five-Lobed Necklace, and Desert Plant (one of the few named pieces in Asawa’s oeuvre.) All four are featured in the Ruth Asawa Retrospective now on display at the San Francisco Museum of Art. The exhibition includes twelve large rooms, so the sheer scale is exhausting. When I visited on Thursday, August 14, 2025, the space was densely crowded and it was great to see so many people--so many different kinds of people--admiring Asawa’s art.

Bronze Wire Circle is a wall piece. It can be seen as an illustration of Bejan’s Constructal Law—or as a cluster of fragile, leafless branches. It invites viewers to see the parallels between the shapes of branches and roots, or between arteries and nerves, or between riverbeds and canyons. We are encouraged to recognize the oneness of nature—and to appreciate its formal and functional beauties.

Gold Wire Crown recalls not only aristocratic adornment, but also the collars of Dutch burghers immortalized by Rembrandt and Frans Hals. Many European jewelry forms are circular: necklaces, bracelets, rings, etc. And when the artist pairs the circular shape with the material of gold, the references are clear. But this work also functions on a purely formal level: The circle is often considered the “perfect” form of geometry since it is totally symmetrical and all points on the circumference are the same distance from the center. Indeed, most of Asawa’s works are not only evocative of “real-world” references, but also resolutely formal abstractions.

Speaking of references to historic jewelry paired with formal vigor, the Five-Lobed Necklace does both magnificently. Perhaps most compelling is the way its translucent shape creates spectral shadows behind it. The sculpture incorporates the wall as a fourth dimension, enhancing its power and mystery.

Desert Plant is a lithograph created at Tamarind Lithographic Studio. Founded by the amazing artist June Wayne and named after the Hollywood street on which her LA studio was located, Tamarind reinvigorated printmaking for the late twentieth century. One artist who spent extended time there was Joseph Albers (who, it will be remembered, was an important teacher for Asawa at Black Mountain College.) June Wayne always spoke of the important collaborative nature of printmaking, so it would naturally appeal to an artist like Asawa who was deeply engaged in working with others whether they be her children, her students, or her artist colleagues.

I mentioned seeing big crowds at the SFMOMA Retrospective. I remember thinking at the time that Asawa should be named the Artist Laureate of San Francisco. But now that I’ve had time to see the exhibition, read the (huge and much-too-heavy) catalogue, as well as write this essay, I vote for Ruth Asawa to be the Artist Laureate of the whole state of California.

N.B. The evening I finished writing this essay, I happened to tune in to the Ken Burns documentary about Leonardo da Vinci on PBS. It made me realize how interested Leonardo has been in Constructal Law (even if that term hadn’t been created yet). Like Asawa, Leonardo saw the similarities in natural forms, from rivers to human nerves. The Italian recorded these treelike similarities in his manuscripts, whereas Asawa built them out of wire. Technically, their approaches were quite different, but they shared a profound interest in the oneness of nature. BAB

Photos by Betty Ann Brown at SFMOMA On view through September 2, 2025